Rooted in Slavery

-

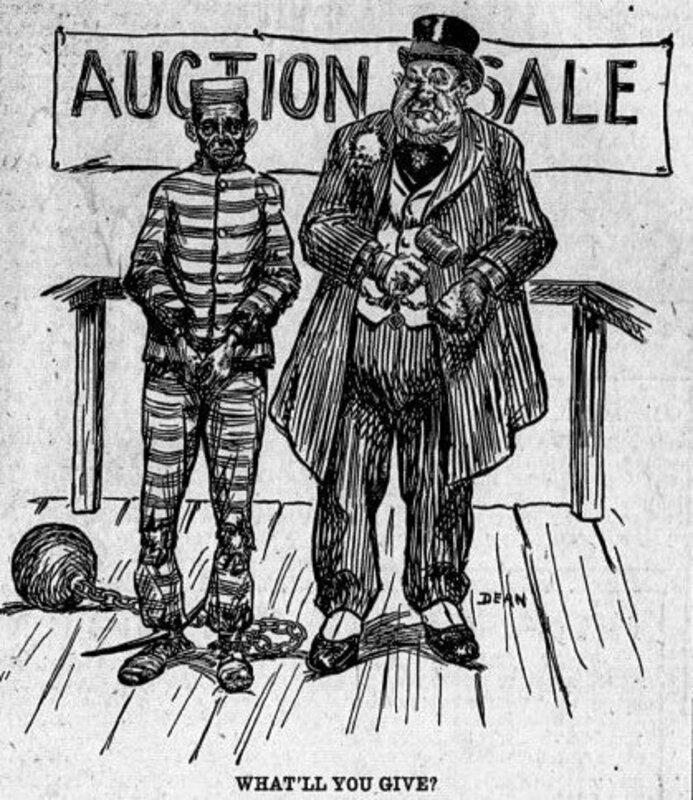

Illustration that depicts the auctioning of a prisoner for his labor, reminiscent of slave auctions. Titled “What'll You Give?,” Atlanta Georgian and News, July 27, 1908, p. 1.

Courtesy of Georgia Newspaper Project, Georgia Historic Newspapers.

-

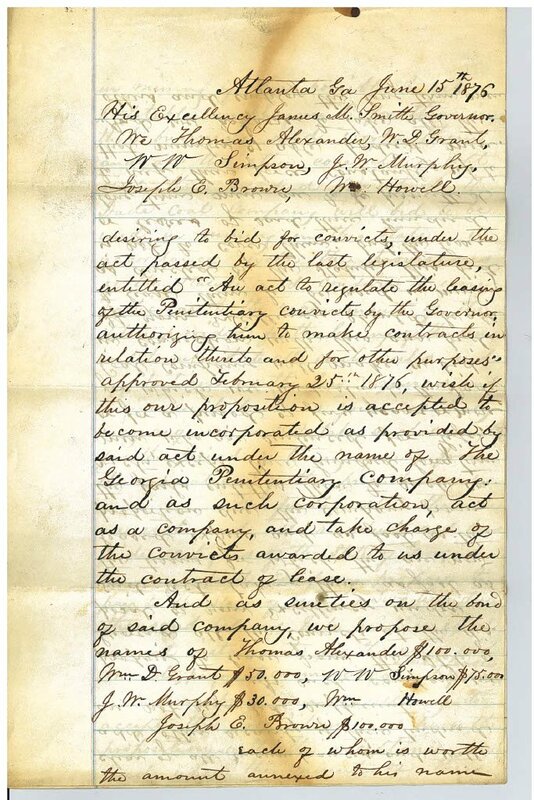

Convict lease bid submitted by Joseph E. Brown for the use of prisoners at Dade Coal Mine. He proposes to hire all of the Penitentiary life convicts for a period of 20 years, “$20.00 per head, per annum.”

Courtesy of Hargrett Library, Joseph E. Brown papers, ms95.

-

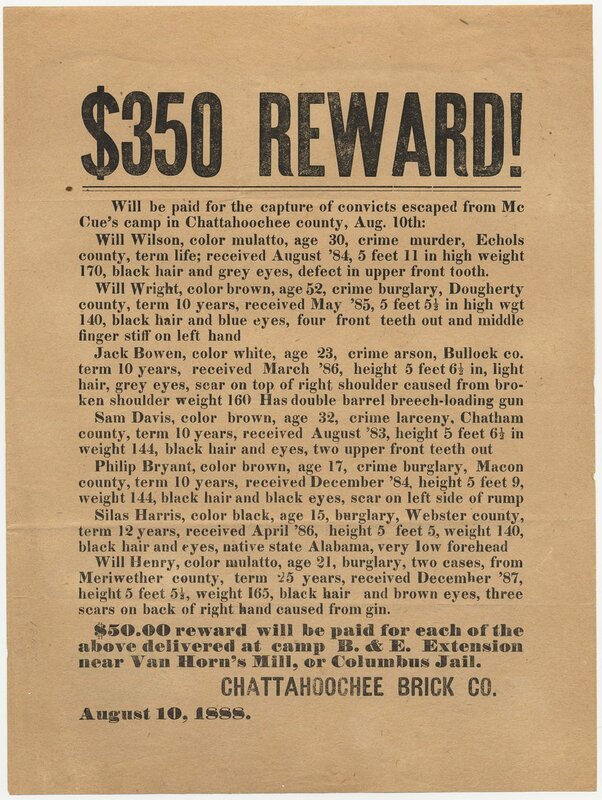

Reward poster for seven prisoners who escaped in 1888 from the Chattahoochee Brick Co., which was known as a death camp.

Courtesy of Hargrett Library, Historical Broadsides Collection.

Georgia’s convict lease system racialized labor from its start. The first prison labor contract in 1868 leased only African American prisoners to the Georgia and Alabama Railroad. Signed by military governor General Thomas Ruger, the agreement assured the company “one hundred able-bodied and healthy Negro convicts.”

Reminiscent of white overseers directing the enslaved, white wardens and Black convicts became frequent subjects of newspaper reports and journal articles. Some of these illustrations attempted to expose the system’s underlying prejudices. More often, however, they were used to advance notions of Black criminality. Under the South's Black Codes, freedpeople too often found themselves arrested for petty crimes like vagrancy. The laws forced freedpeople to enter into labor contracts with their former enslavers; those who refused were sent to the chain gang for the crime of “unemployment.” The system targeted Black communities and sent hundreds of Black men and women, some only adolescents, to camps for minor offenses. As a result, Black inmates, and especially young Black men, vastly outnumbered all other prisoners.

Prisoners often risked their lives, and the lives of fellow inmates, to escape the cruel treatment and backbreaking labor of Georgia’s convict camps. Escapees were tracked by bloodhounds and sought after in newspaper “wanted” advertisements and posted broadsides offering generous rewards for their capture. These tactics were not unlike those employed by enslavers searching for fugitives from slavery.