Child Welfare Reform

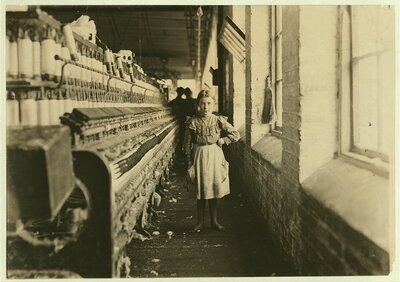

In the New South era, danger lurked in industrializing cities and towns that were rapidly altering the state’s pastoral landscape. Female reformers were particularly concerned about the threat these dangers posed for children who were often vulnerable to modern changes: child laborers were injured and maimed in textile factories; students were crammed into overcrowded, poorly-ventilated classrooms; and neighborhood children played in unsupervised city streets littered with trash. Through grassroots crusades, mutual aid and civic organizations, and local campaigns, southern women refashioned their traditional gender roles and invoked their maternal duties as mothers to justify their influence over a wide range of political issues related to the health and welfare of children. These reformers rebranded themselves as “municipal housekeepers” responsible for improving conditions for children, built an array of programs, and lobbied for legislation that expanded public education, prohibited child labor, enforced sanitation standards in schools and neighborhoods, developed playgrounds and recreational facilities, and created juvenile justice systems and orphanages. The reform efforts of Georgian women in the Progressive Era culminated in countless public services and laws that laid the groundwork for a state child welfare system that still exists today.