The Hope and Failure of Reconstruction

-

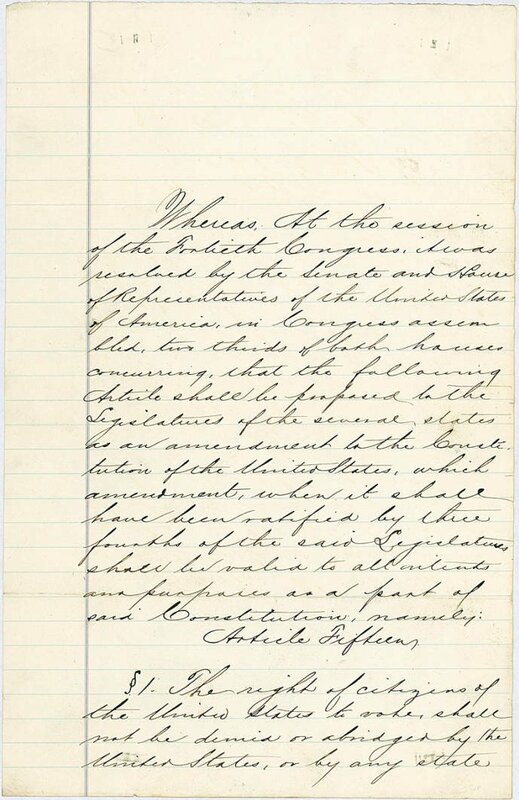

In order to reenter the Union during Reconstruction, the Georgia General Assembly ratified the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870. The Fifteenth Amendment guaranteed formerly enslaved people the right to vote, but white supremacists kept this promise from being fully true until Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Courtesy of the Georgia Archives, Enrolled Acts and Resolutions, House and Senate, Legislature, RG 37-1-15.

-

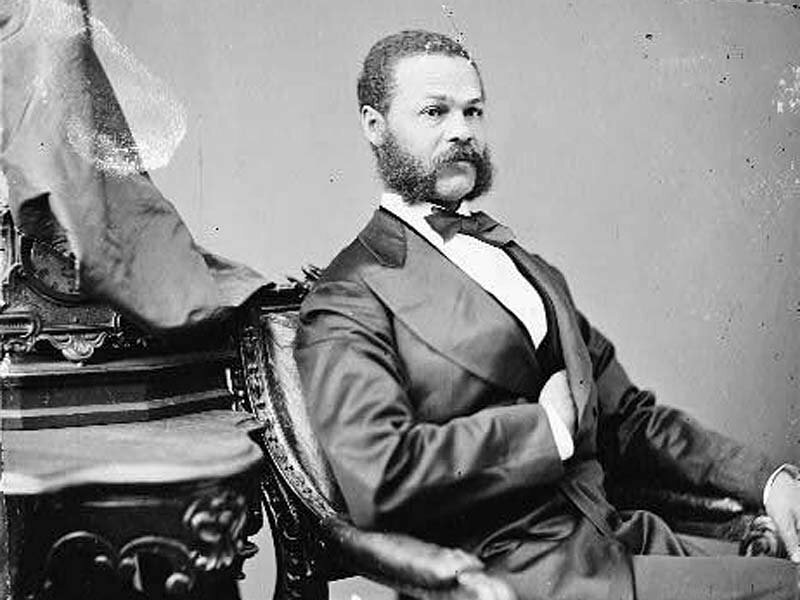

Jefferson Franklin Long was the first Black person to represent Georgia in the U.S. House of Representatives. He served only four months before the legislative term ended, and Georgia did not have another Black representative until Andrew Young's election in 1972.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, via New Georgia Encyclopedia.

-

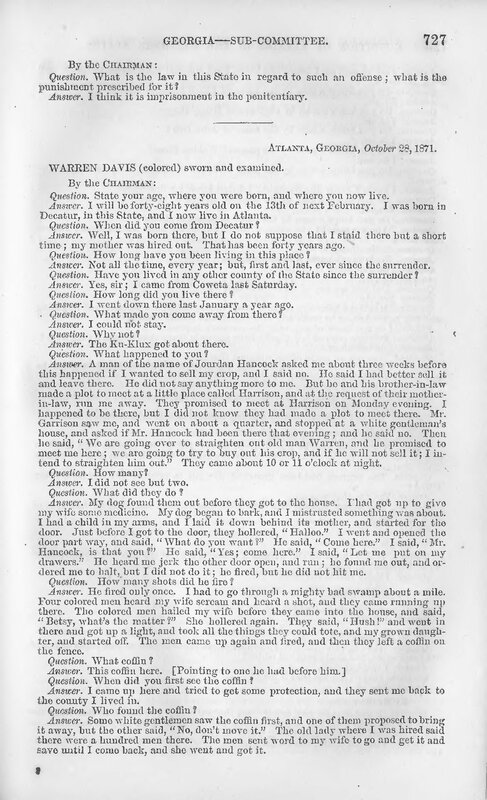

Warren Davis was a Black man who lived in Coweta County before the Ku Klux Klan attacked him and his family in 1870. Davis was one of many Black victims of racial violence during this period.

Courtesy of University of Georgia. Map and Government Information Library, Georgia Government Publications.

-

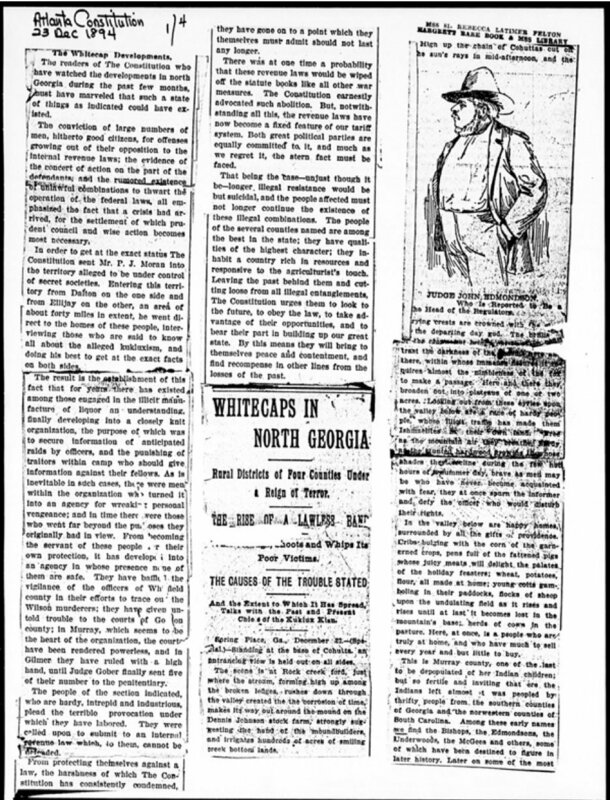

White-capping was a problem in the north Georgia mountains during the late 19th century. Mobs of poor whites would terrorize their enemies--racial, economic, or otherwise--by night.

Courtesy of Hargrett Library, Rebecca Latimer Felton papers, ms 81.

The war's end afforded new opportunities to African Americans in Georgia. General William T. Sherman had promised “forty acres and a mule” to former bondsmen in the conflict’s final days, and the Freedmen’s Bureau established local offices around the state to help secure food, shelter, and education for Black Georgians. Thirty-three Black men even joined the state legislature thanks to the votes of freedmen, but full citizenship remained an illusory promise. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) launched a massive campaign of violence to keep Black men from exercising their right to vote, which helped the ex-Confederate “Redeemers” expel the Black legislators in 1868 and then take control of the state government shortly after it reentered the Union in 1870.

After Reconstruction, conditions only worsened for African Americans. The new convict lease system allowed the state to lease prisoners to private businesses, and racial inequalities in the justice system meant that Black convicts performed much of the work to rebuild the region and its economy. By the 1890s, Black Georgians had little political representation and no voting rights.